成为一个中世纪的国王会是什么感觉?

正文翻译

What would it have been like to be a medi king?

成为一个中世纪的国王会是什么感觉?

成为一个中世纪的国王会是什么感觉?

评论翻译

Stephen Tempest

, MA Modern History, University of Oxford (1985)

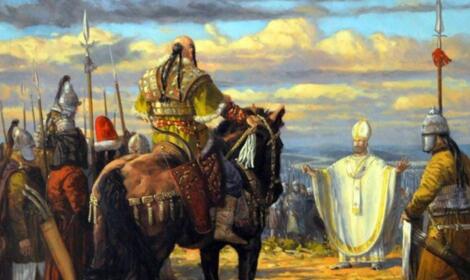

Media kings spent a lot of time travelling around their realm from place to place. One of the duties of a vassal was offering hospitality to the king and his entourage if he chose to pay a visit - which could get very expensive, since kings always travelled with a large number of guards, ministers, servants and companions befitting their status. Indeed, one of the purposes of such visits was to make sure the subjects were reminded who their king was, and to give him the opportunity to inspect things in person.

Still, for the purpose of this descxtion we'll assume the king is at home in one of the castles he owns. We'll also assume we're talking about a Western European king in the High Middle Ages (1200-1350, or thereabouts).

The king or lord of a castle, and his wife, were often the only people to have a private bedroom of their own - and even here 'private' is a relative term, since it was normal for a servant or two to spend the night on a pallet bed in the same room, in case the king woke during the night and needed them. This bedroom was called the 'solar' since it was usually constructed high in the great tower of a keep, with windows to let the sunlight in. The walls would likely be stone, whitewashed or plastered, and hung with tapestries to keep out the draughts. The floor would be wooden; carpets had not been introduced yet in Europe.

As time went by, it became more common for high-ranking members of the household to have separate bedrooms; but it was not yet standard. Most people slept communally in the Great Hall, or in the case of servants on the floor of their own workplace (kitchen, stable, etc).

The king's bed was wooden - and capable of being dismantled so the king could take it with him when going on a journey. The springs would be made of leather or rope, the mattress and pillows of linen stuffed with goose-feathers, and the bed was normally of the 'four-poster' design with linen curtains that could be pulled across to give the illusion of privacy from the servants sleeping a couple of metres away. It seems that people usually slept naked (those who could afford warm beds, at any rate).

A canopied media bed - this picture dates from about 1400, and shows Queen Guinevere dragging Sir Lancelot into her bed.

On waking, the king and queen would wash their hands and face in a bowl of water brought up to the bedroom by a servant. The toilet ('privy chamber') was usually a small room built into the tower wall, with a simple hole in a seat overhanging the moat. Having a bath or shower was not something done as a daily routine - heating and carrying all that water up from the well in buckets was very labour-intensive, so baths were considered a special treat.

The king would then get dressed, either by himself or with the aid of servants. Typical undergarments would be a pair of linen 'braies' (baggy underpants, fastened around the waist by a cord tie), woollen 'hose' (stockings, which attached to the same cord tie as the underwear), and perhaps a linen 'chemise' (shirt). Then over this came a tunic, which was normally a full-length garment with long, baggy sleeves that pulled on over the head and hung down to the ground. This was a status symbol - people who had to work for a living wore shorter tunics that left their legs free. Also, while most tunics - even for nobility - were made of wool, a king might wear a tunic of silk or velvet or even cotton (which was more expensive than silk) to show off his wealth. A second tunic or 'surcoat' was often worn over the first one - it was generally shorter, with short, wide sleeves, and the fashion-conscious would make sure that the colours of the over-tunic and under-tunic complemented each other. Finally, a hood or mantle would be fastened around the neck - while this could be pulled up over the head to keep your ears warm, its primary purpose was actually decorative; they could be trimmed with expensive fur or jewels. Shoes and a belt completed the ensemble. There were no pockets - you tucked things into your sleeves, or hung a pouch from your belt.

Women's clothes were not much different to men's at this time, except that instead of a shirt and breeches, their undergarment was a linen shift. A woman's surcoat was often sleeveless, and sometimes cut away at the sides, to emphasise her figure. Also, married women were expected to cover their hair when in public, with a cloth scarf, hat or wimple; unmarried women kept their hair uncovered, often with jewelled clips in it.

Clothing styles for the nobility circa 1300 - an ankle-length long-sleeved tunic, with a second surcoat with short or no sleeves worn over the top of it.

After dressing, the king would go to his private chapel, where he would hear Mass. He might then go down to the Great Hall to break his fast (that is, have breakfast) with his nobles and attendants. This was normally simple; bread and beer. (Very weak beer, not something you could easily get drunk on.) Many people did not eat breakfast at all, but instead waited until dinner, which was generally served early at about 11:00 in the morning.

The Great Hall usually covered the entire first floor of the castle (the ground floor was used for storage, and had no doors or windows for defensive reasons). There would be a fireplace either in the centre of the room or against one wall. A raised dais was at one end of the hall (furthest from the entrance) where the king's throne would be set, sometimes with a canopy over it, along with less-impressive chairs for his family, honoured guests, and most important advisors. At mealtimes, benches and trestle tables would be set up in the hall, and the tables covered in clean white cloths. Afterwards, the benches could be pushed to the sides of the room to make space - and at night many of the castle staff, even those of high rank, would sleep on those benches.

There was no set routine for the king's day, but a conscientious ruler would have plenty of official business to take care of. This can be divided into two categories - affairs of state and estate management.

The king might have policy discussions with his Council - the most powerful barons and bishops of the realm, and his chief ministers such as the Treasurer, the Chancellor and the Marshal. He would issue commands, that were noted down by royal clerks. He might administer justice - the king was considered the chief judge of the kingdom, and while this task was normally delegated the king reserved the right to hear cases in person. He might hear petitions and appeals from his subjects, and requests for him to grant them a favour or use his power on their behalf. As a rule, the latter two tasks were reserved for special occasions - the king would hold court in a castle or hall, and summon his nobles and people to appear before him so he could 'seek their advice and counsel' and dispense justice. These formal meetings would eventually develop into the institution of Parliament.

Estate management was vital because the king was the largest landowner in the country. Contrary to popular belief, most of the royal income in media times did not come from taxes (which were normally only levied in national emergencies such as a war) but from tolls, rents and income from the king's tenants and those making use of his property. Overseeing his tenants and managing the income was a major job, and a responsible king would spend a lot of time with his stewards going over the accounts and supervising their decisions.

If the king had no official business to conduct that day, he might instead go hunting - a very popular pastime with the nobility. Most hunting was done from horseback, with the quarry being deer or perhaps wild boar. A professional huntsman with a team of dogs would flush out the quarry and corner it, then the king or his guests and companions would kill the prey with a spear or bow and arrow. Hawking and falconry were also popular pastimes - for ladies as well as knights. The prey killed would usually find its way to the royal table at dinnertime.

The main meal of the day was normally started early, before midday, and would go on for a couple of hours. Elaborate rituals and etiquette surrounded the meal; it was an important way for the king to demonstrate his wealth and status, and do honour to his important guests. The seating arrangement for a meal was determined according to rigid rules of precedence - the more important you were, the closer to the king you were sat. Women and men would be interspersed where possible.

Media dinnertime, from the Luttrell Psalter

It was considered polite to wash your hands before eating; a bowl of water might be set out next to the entrance to the hall to allow this, or the servants would bring ewers of water to each guest. Washing your hands between courses was also important - since the fork had not yet been invented, so people picked food up with their fingers. (Though spoons were used for soup and broth, and knives for cutting.)

Rather than plates, food was often eaten from 'trenchers', which were large, thick slices of slightly stale bread. These soaked up the juices from the food, and if you were especially hungry you could eat them as well. The meal would have multiple courses, and each course would often see several different dishes placed on the table, from which you could sext as much or as little as you liked of each. It was considered polite to serve the person sitting next to you before yourself, if they were of a higher rank than you.

The first course of the meal was often boiled or stewed meat - pork, chicken, mutton and venison being most common - prepared with an elaborate range of strongly-flavoured sauces, herbs and spices. On fast days, fish was served instead of meat - eels and lampreys, herring or pike, with more of the elaborate sauces and dressings. After the first course, fruit or nuts might be served to clear the palate.

The second course would be roast meat - often venison or game from the hunters, although this was an opportunity for extravagant hosts to impress their guests by serving exotic meat - roast peacock, for example. Salmon, turbot or lampreys might be served on fish days. Vegetables such as leeks, onions, peas and beans would accompany the meat, though often incorporated into sauces and pottages rather than being served separately. Bread was also served, and was often graded into qualities (the whiter the bread, the better) and given to guests of the appropriate status.

The third course would be fruit-based dishes - quinces, damsons, apples, pears, other fruits depending on season; often baked or candied or made into compotes. Small, expensive meat dishes might also be served such as roast sparrows or pickled sturgeon. Finally, cheese would be served at the end of the meal.

To drink, there would be either wine or beer. Wine was considered the higher status drink, so you could expect it to be served at a royal banquet - while the servants and lesser guests would get beer. By modern standard media wine was very rough; it had to be drunk the same year it was made (no corks and no glass bottles). As a point of interest, in the year 1363 King Edward III of England's royal household got through 170,310 gallons of wine, most of it shipped over from Bordeaux.

Both during and after the meal there would be entertainment. Jesters actually did exist; from what we know of the media sense of humour people tended to enjoy slapstick, sarcasm and practical jokes, and could be rather cruel in their humour. Actors, jugglers and acrobats might also be hired to provide entertainment. Music, however, was perhaps more common; musicians would play lutes or harps or other instruments, and minstrels would sing songs and ballads. After the meal was over some of the nobles present might also give a performance of a song or poem, if they had the talent. Composing your own poem was considered a notable achievement - though we know that some noblemen paid professional troubadours to write songs for them, which they then passed off as their own!

A group of Italians from Siena dancing in about the year 1340, to the music of a tambourine.

There might also be dancing once the tables were pushed aside. Party games such as blind man's buff were popular. Less energetic nobles might play chess or backgammon, or gamble with dice. Playing cards reached Europe towards the end of the 14th century. As for sport, bowling became so popular in the 14th century that several kings tried (unsuccessfully) to ban it since it interfered with archery practice. Jeu de paume, the ancestor of tennis, was also popular - it was played with a gloved hand rather than a racket. Football was considered a peasants' game, and cricket hadn't yet been developed. Various martial practices such as fencing, tilting (jousting practice) and archery might also be engaged in. People might also go for a walk or a ride outside if the weather was fine.

The second meal of the day would be served at the end of the afternoon, being smaller and simpler than dinner. The evening was usually spent relaxing; and people generally went to bed early so they could be up first thing in the morning, and make maximum use of daylight.

,牛津大学现代史硕士(1985)

中世纪的国王们花了很多时间在他们的王国里穿梭,从一个地方到另一个地方。臣子的职责之一是在国王带着随行人员选择性访问时提供招待--这可能会非常昂贵,因为国王总是带着与他们地位相称的大量卫兵、大臣、仆人和同伴一起旅行。事实上,这种访问的目的之一是确保臣民们知道他们的国王是谁,并让他有机会亲自视察领地。

不过,为了便于描述,我们将假设国王在他所拥有的某个城堡的家中。我们还假设我们谈论的是中世纪盛期(1200-1350年左右)的西欧国王。

城堡里的国王或领主,以及他的妻子,往往是唯一拥有自己的私人卧室的人--即使在这里,"私人"也是一个相对的术语,因为通常会有一两个仆人在同一房间的小床上过夜,以防国王在夜间醒来有什么需要。这间卧室被称为"solar(太阳能)",因为它通常建在堡垒的大塔高处,有窗户让阳光照射进来。墙壁可能是石头的,粉刷过或抹过灰,并挂着挂毯以防止气流进入,地板是木头的;当时欧洲还没有引进地毯。

随着时间的推移,家庭中的高级成员拥有独立的卧室变得越来越普遍;但这还是没有成为标准。大多数人都睡在大殿里,如果是仆人,则睡在他们自己工作场所(厨房、马厩等)的地板上。

国王的床是木制的--而且可以拆卸,以便国王在旅行时可以带着它。弹簧是用皮革或绳索制成的,床垫和枕头是用鹅毛填充的亚麻布,床通常是"四柱"设计,亚麻布窗帘可以拉开,让人觉得跟睡在几米外的仆人有点隐私。似乎人们通常都是裸睡的(不管怎么样,对于那些买得起暖床的人来说)。

一张带顶篷的中世纪床——这张画像的历史可追溯至 1400 年左右,展示了桂妮维亚女王将兰斯洛特爵士拽到她的床上。

醒来后,国王和王后会在仆人端到卧室的一碗水中洗手和洗脸。厕所("privy chamber")通常是建在塔楼墙壁上的一个小房间,上面有一个简单的孔,座位悬在护城河上。洗澡或淋浴并不是每天都要做的事情--加热和用水桶从井里提水是非常费力的,所以洗澡被认为是一种特殊的待遇。

然后,国王会自己或在仆人的帮助下穿上衣服。典型的内衣是一双亚麻布"胸罩"(宽大的内裤,用绳子系在腰上)、羊毛"长筒袜"(长筒袜与内衣一样用绳子系着),也许还有一件亚麻布"罩衫"(衬衫)。然后是外衣,这通常是一件袖子又长又宽的及地的衣服,从头上套入,一直垂到地上。这是一种身份的象征--需要工作的人才穿较短的外衣,让他们的腿部可以自由活动。另外,虽然大多数外衣--即使是贵族的外衣--都是由羊毛制成的,但国王可能会穿一件丝绸或天鹅绒甚至棉花(比丝绸更昂贵)的外衣来炫耀他的财富。第二件外衣或"surcoat "通常穿在第一件外衣外面--它通常整体比较短,袖子又短又宽,有时尚意识的人会确保上衣和下衣的颜色相得益彰。最后,在脖子上系上头巾或斗篷--虽然这可以拉到头上来让耳朵保暖,但它的主要目的实际上是装饰;它们可以用昂贵的毛皮或珠宝来修饰。再穿上鞋子和束上腰带,就完成了这套衣服的穿搭。没有口袋--你可以把东西塞进袖子里,或在腰带上挂一个小袋子。

这个时候女性的衣服和男性的衣服没有什么不同,只是她们的内衣不是衬衫和马裤,而是亚麻布的短裤。妇女的外衣通常是无袖的,有时还在两侧剪开,以突出她的身材。此外,已婚妇女在公共场合要用布围巾、帽子或头巾遮盖头发;未婚妇女则不遮盖头发,经常用珠宝夹夹住头发。

1300年左右的贵族服装风格--长及脚踝的长袖外衣,外面再穿一件短袖或无袖的外衣。

穿好衣服后,国王会去他的私人小教堂,在那里聆听弥撒。然后,他可能会到大殿与他的贵族和随从一起开斋(即吃早餐)。这通常很简单:面包和啤酒。(非常淡的啤酒,不是你灌两瓶就会醉那种。)许多人根本不吃早餐,而是等到晚餐时再吃,而晚餐一般在早上11点左右提前供应。

大厅通常覆盖城堡的整个一楼(一楼用于储存,出于防御的目的,没有门窗)。房间的中央或靠墙的地方会有一个壁炉。大厅的一端有一个高台(离入口最远处),国王的宝座就摆在那里,有时上面还有一个天幕,还有为他的家人、尊贵的客人和最重要的顾问准备的不太引人注目的椅子。用餐时,大厅里会摆放长椅和木桌,桌子上铺着干净的白布。之后,长椅可以被推到房间的两侧以腾出空间--晚上,许多城堡的工作人员,甚至是那些高官,会睡在这些长椅上。

国王的一天没有固定的作息时间,但一个有良知的统治者会有很多公务要处理。这可以分为两类--国家事务和庄园管理。

国王可能会与他的议会--王国中最有权势的男爵和主教,以及他的首席部长,如司库、大法官和元帅,进行政策讨论。他将发布命令,并由皇家文员记录下来。他可以主持正义--国王被认为是王国的首席法官,虽然这项任务通常被委托给别人,但国王保留了亲自审理案件的权利。他可以听取臣民的请愿和申诉,以及要求他给予他们恩惠或代表他们使用权力的请求。通常情况下,后两项任务是为特殊场合保留的--国王会在城堡或大厅里开庭,并召集他的贵族和人民到他面前,以便他能"征求他们的意见和建议"并主持正义。这些正式会议最终发展成为了议会制度。

庄园管理是至关重要的,因为国王是全国最大的土地所有者。与人们的普遍看法相反,中世纪的皇家收入大多不是来自税收(通常只有在战争等国家紧急情况下才会征收),而是来自国王的佃户和使用其财产的人的过路费、租金和收入。监督佃户和管理收入是一项重要的工作,一个负责任的国王会花很多时间和他的管家一起查看账目并监督他们的决策。

如果国王当天没有公务要做,他可能会去打猎--这是一种非常受贵族欢迎的消遣方式。大多数打猎是在马背上进行的,猎物是鹿或野猪。一个专业的猎手带着一队狗将猎物赶出来,然后国王或他的客人和同伴将用长矛或弓箭杀死猎物。鹰猎和猎鹰也是很受欢迎的消遣方式--对于女士和骑士来说都是如此。杀死的猎物通常会在晚餐时间出现在皇家的餐桌上。

一天中的主餐通常很早,在正午之前就开始了,并会持续几个小时。会有精心设计的仪式和礼仪围绕着这顿饭;这是国王展示其财富和地位的重要方式,也是对重要客人的尊重。吃饭时的座位安排是根据严格的优先规则决定的--你越是重要,你坐得越靠近国王。在可能的情况下,女性和男性会穿插坐在一起。

中世纪的晚餐时间,来自勒特雷尔诗篇

吃饭前洗手被认为是一种礼貌;在大厅的入口处可能会摆放一碗水,以便于洗手,或者仆人会给每个客人送上水壶。在两道菜之间洗手也很重要--因为当时还没有发明叉子,所以人们用手指拿起食物。(虽然汤和肉汤用的是勺子,切菜用的是刀子)。

人们通常不使用盘子,而是用"掘沟"来吃食物,掘沟是又大又厚的略显陈旧的面包片。这些面包吸收了食物的汁液,如果你特别饿,你也可以吃这些面包。这顿饭有多道菜,每道菜往往会被分成几盘放在桌子不同的位置,你可以从中选择你喜欢的每道菜,或多或少。如果坐在你旁边的人的地位比你高,那么在你自己之前为他们服务被认为是一种礼貌。

第一道菜通常是煮或炖的肉--猪肉、鸡肉、羊肉和鹿肉最常见--用各种味道浓郁的酱汁、草药和香料精心准备。在禁食日,人们用鱼来代替肉--鳗鱼和灯鱼、鲱鱼或梭鱼,并配以更多精心制作的酱料和调味品。在第一道菜之后,可能会提供水果或坚果来清理味觉。

第二道菜是烤肉--通常是鹿肉或来自猎人的猎物,这也是奢侈的主人通过提供异国情调的肉类--例如烤孔雀--来给他们的客人留下深刻印象的机会。鲑鱼、多宝鱼或灯笼鱼可能会在捕鱼日被供应。韭菜、洋葱、豌豆和豆类等蔬菜会与肉一起食用,但通常会被纳入酱汁和摆盘中,而不是单独食用。面包也有供应,而且通常按质量分级(面包越白越好),并提供给有适当地位的客人。

第三道菜是以水果为主的菜肴--榅桲、李子、苹果、梨,以及其他取决于季节的水果;通常是烘烤、蜜饯或做成果酱。小而昂贵的肉类菜肴也可能被供应,如烤麻雀或腌制鲟鱼。最后,在用餐结束时还会提供奶酪。

饮料方面,有葡萄酒或啤酒。葡萄酒被认为是地位较高的饮料,所以你可以期待在皇室宴会上有葡萄酒的供应--而仆人和地位较低的客人则会得到啤酒。按照现代标准,中世纪的葡萄酒是非常粗糙的;它必须在酿造的当年就喝掉(没有瓶塞,没有玻璃瓶)。有趣的是,在1363年,英国国王爱德华三世的王室用了170310加仑的葡萄酒,其中大部分是从波尔多运过来的。

在用餐期间和用餐之后,都会有娱乐活动。宫廷小丑确实存在;根据我们对中世纪幽默感的了解,人们往往喜欢滑稽、讽刺和实用的笑话,而且他们的幽默可能相当残酷。演员、杂耍者和杂技演员也可能被雇用来提供娱乐。然而,音乐也许更常见;音乐家会弹奏琵琶或竖琴或其他乐器,吟游诗人会演唱歌曲和歌谣。宴会结束后,一些在场的贵族如果有天赋,也可能会表演一首歌或一首诗。创作自己的诗歌被认为是一项显著的成就--尽管我们知道有些贵族付钱给专业的吟游诗人为他们写歌,然后他们把这些歌当作自己的歌!

大约在1340年,一群来自锡耶纳的意大利人伴随着手鼓的音乐跳舞。

等到桌子被推到一边,可能还会有舞蹈。派对游戏,如捉迷藏,很受欢迎。没有那么多精力的贵族可能会玩国际象棋或双陆棋,或者用骰子赌博。14世纪末,扑克牌传到了欧洲。在体育方面,保龄球在14世纪变得如此流行,以至于一些国王试图禁止它,因为它干扰了射箭的练习,但没有成功。网球的祖先“Jeu de paume”也很流行--它是用戴着手套的手而不是用球拍来打球。足球被认为是农民的游戏,而板球还没有发展起来。人们还可能从事各种武术练习,如击剑、摔跤和射箭。如果天气好,人们还可能到外面散步或骑马。

一天中的第二顿饭将在下午结束时供应,比晚餐要少而简单。晚上通常是在放松中度过;人们一般都会早早上床睡觉,以便在早上第一时间起床,最大限度地利用白天的时间。

Pad Murray

So during this period how would the King work meetings with the parliament into his schedule? Did he go to Westminster on a regular basis, would they come to him (daily, weekly, etc), or did he only meet them when he absolutely needed to?

那么,在这一时期,国王是如何将与议会的会面纳入他的日程安排的?他是否定期去威斯敏斯特,臣子是否会定时来找他(每天、每周等),或者只有在国王有绝对需求的时候才会见他们?

Stephen Tempest

Media parliaments were special events, not a permanent institution. The king would summon a parliament to wherever he happened to be staying that year — it wasn't until the 1400s that Westminster became the regular place for them to be held.

Personal invitations ('writs of summons') would go out to the most important lords and bishops, and sheriffs would be ordered to organise elections. Usually between 1 to 3 months later everyone would assemble. There'd be lots of ceremony as the king welcomed them, they paid allegiance to him, and he told them what he's summoned them for (almost inevitably, this would be "I need money").

As I understand it,. when Parliament was in session the king would normally sit with the Lords discussing affairs with them; the Commons would meet separately and submit petitions and draft bills for the consideration of the king. This was as much due to numbers as questions of social status (though that was important too); there were normally fewer than 50 lords present with the king, so it would be a working meeting.

Parliament would usually only be in session for a month or two. Then the king would dissolve it and everybody would go home again. There was no rule on how often Parliament should be summoned; in wartime it tended to be fairly regular (yearly or at least every couple of years), in peacetime multiple years might go by before there was a need for another parliament.

中世纪的议会是特殊事件,而不是一个永久性的机构。国王会在他当年碰巧停留的地方召集议会--直到14世纪,威斯敏斯特才成为举行议会的固定地点。

个人邀请函("传票")会发给最重要的领主和主教,治安官会被命令组织选举。通常在1至3个月后,所有人都会聚集在一起。当国王欢迎他们时,会有很多仪式,他们向国王效忠,国王告诉他们他召集他们的原因(几乎不可避免的是,这将是 "我需要钱")。

据我所知,当议会开会时,国王通常会与上议院坐在一起讨论事务;下议院会单独开会,提交请愿书和法案草案供国王审议。这既是由于人数问题,也是由于社会地位问题(尽管这也很重要);与国王一起出席的上议院议员通常少于50人,所以这将是一次工作会议。

议会通常只开一两个月的会。然后,国王就会解散议会,大家又会回家了。没有关于议会应多长时间召开一次的规定;在战争时期,议会往往是相当定期的(每年或至少每两年一次),在和平时期,在需要召开另一次议会之前,可能距离上一次已经过去多年。

Diana Dubrawsky

I was taught in college that one way the king collected taxes was by traveling about and making his nobles pay for the court's upkeep: makes sense, since many eataes were "cash poor." The cost of feeding the entourage could be ruinous, and if a king really wanted to bankrupt his vassal, he could extend the court's stay indefinitely.

我在大学里接受的教育是,国王收税的一种方式是通过旅行,让他的贵族们支付宫廷的维持费用:这是有道理的,因为许多国王是"现金穷人(名义上富有,但是拿不出很多现金)"。养活随行人员的费用可能会很高,如果国王真的想让他的臣子破产,他可以无限期地延长宫廷的逗留时间。

Stephen Tempest

True - though the idea of bankrupting a noble by staying with them over-long is something I associate more with the Tudors (Elizabeth I in particular) than media kings.

确实如此--尽管通过长期与贵族呆在一起而使其破产的想法,我会更多地将其与都铎王朝(尤其是伊丽莎白一世)联系起来,而不是与中世纪的国王联系起来。

, MA Modern History, University of Oxford (1985)

Media kings spent a lot of time travelling around their realm from place to place. One of the duties of a vassal was offering hospitality to the king and his entourage if he chose to pay a visit - which could get very expensive, since kings always travelled with a large number of guards, ministers, servants and companions befitting their status. Indeed, one of the purposes of such visits was to make sure the subjects were reminded who their king was, and to give him the opportunity to inspect things in person.

Still, for the purpose of this descxtion we'll assume the king is at home in one of the castles he owns. We'll also assume we're talking about a Western European king in the High Middle Ages (1200-1350, or thereabouts).

The king or lord of a castle, and his wife, were often the only people to have a private bedroom of their own - and even here 'private' is a relative term, since it was normal for a servant or two to spend the night on a pallet bed in the same room, in case the king woke during the night and needed them. This bedroom was called the 'solar' since it was usually constructed high in the great tower of a keep, with windows to let the sunlight in. The walls would likely be stone, whitewashed or plastered, and hung with tapestries to keep out the draughts. The floor would be wooden; carpets had not been introduced yet in Europe.

As time went by, it became more common for high-ranking members of the household to have separate bedrooms; but it was not yet standard. Most people slept communally in the Great Hall, or in the case of servants on the floor of their own workplace (kitchen, stable, etc).

The king's bed was wooden - and capable of being dismantled so the king could take it with him when going on a journey. The springs would be made of leather or rope, the mattress and pillows of linen stuffed with goose-feathers, and the bed was normally of the 'four-poster' design with linen curtains that could be pulled across to give the illusion of privacy from the servants sleeping a couple of metres away. It seems that people usually slept naked (those who could afford warm beds, at any rate).

A canopied media bed - this picture dates from about 1400, and shows Queen Guinevere dragging Sir Lancelot into her bed.

On waking, the king and queen would wash their hands and face in a bowl of water brought up to the bedroom by a servant. The toilet ('privy chamber') was usually a small room built into the tower wall, with a simple hole in a seat overhanging the moat. Having a bath or shower was not something done as a daily routine - heating and carrying all that water up from the well in buckets was very labour-intensive, so baths were considered a special treat.

The king would then get dressed, either by himself or with the aid of servants. Typical undergarments would be a pair of linen 'braies' (baggy underpants, fastened around the waist by a cord tie), woollen 'hose' (stockings, which attached to the same cord tie as the underwear), and perhaps a linen 'chemise' (shirt). Then over this came a tunic, which was normally a full-length garment with long, baggy sleeves that pulled on over the head and hung down to the ground. This was a status symbol - people who had to work for a living wore shorter tunics that left their legs free. Also, while most tunics - even for nobility - were made of wool, a king might wear a tunic of silk or velvet or even cotton (which was more expensive than silk) to show off his wealth. A second tunic or 'surcoat' was often worn over the first one - it was generally shorter, with short, wide sleeves, and the fashion-conscious would make sure that the colours of the over-tunic and under-tunic complemented each other. Finally, a hood or mantle would be fastened around the neck - while this could be pulled up over the head to keep your ears warm, its primary purpose was actually decorative; they could be trimmed with expensive fur or jewels. Shoes and a belt completed the ensemble. There were no pockets - you tucked things into your sleeves, or hung a pouch from your belt.

Women's clothes were not much different to men's at this time, except that instead of a shirt and breeches, their undergarment was a linen shift. A woman's surcoat was often sleeveless, and sometimes cut away at the sides, to emphasise her figure. Also, married women were expected to cover their hair when in public, with a cloth scarf, hat or wimple; unmarried women kept their hair uncovered, often with jewelled clips in it.

Clothing styles for the nobility circa 1300 - an ankle-length long-sleeved tunic, with a second surcoat with short or no sleeves worn over the top of it.

After dressing, the king would go to his private chapel, where he would hear Mass. He might then go down to the Great Hall to break his fast (that is, have breakfast) with his nobles and attendants. This was normally simple; bread and beer. (Very weak beer, not something you could easily get drunk on.) Many people did not eat breakfast at all, but instead waited until dinner, which was generally served early at about 11:00 in the morning.

The Great Hall usually covered the entire first floor of the castle (the ground floor was used for storage, and had no doors or windows for defensive reasons). There would be a fireplace either in the centre of the room or against one wall. A raised dais was at one end of the hall (furthest from the entrance) where the king's throne would be set, sometimes with a canopy over it, along with less-impressive chairs for his family, honoured guests, and most important advisors. At mealtimes, benches and trestle tables would be set up in the hall, and the tables covered in clean white cloths. Afterwards, the benches could be pushed to the sides of the room to make space - and at night many of the castle staff, even those of high rank, would sleep on those benches.

There was no set routine for the king's day, but a conscientious ruler would have plenty of official business to take care of. This can be divided into two categories - affairs of state and estate management.

The king might have policy discussions with his Council - the most powerful barons and bishops of the realm, and his chief ministers such as the Treasurer, the Chancellor and the Marshal. He would issue commands, that were noted down by royal clerks. He might administer justice - the king was considered the chief judge of the kingdom, and while this task was normally delegated the king reserved the right to hear cases in person. He might hear petitions and appeals from his subjects, and requests for him to grant them a favour or use his power on their behalf. As a rule, the latter two tasks were reserved for special occasions - the king would hold court in a castle or hall, and summon his nobles and people to appear before him so he could 'seek their advice and counsel' and dispense justice. These formal meetings would eventually develop into the institution of Parliament.

Estate management was vital because the king was the largest landowner in the country. Contrary to popular belief, most of the royal income in media times did not come from taxes (which were normally only levied in national emergencies such as a war) but from tolls, rents and income from the king's tenants and those making use of his property. Overseeing his tenants and managing the income was a major job, and a responsible king would spend a lot of time with his stewards going over the accounts and supervising their decisions.

If the king had no official business to conduct that day, he might instead go hunting - a very popular pastime with the nobility. Most hunting was done from horseback, with the quarry being deer or perhaps wild boar. A professional huntsman with a team of dogs would flush out the quarry and corner it, then the king or his guests and companions would kill the prey with a spear or bow and arrow. Hawking and falconry were also popular pastimes - for ladies as well as knights. The prey killed would usually find its way to the royal table at dinnertime.

The main meal of the day was normally started early, before midday, and would go on for a couple of hours. Elaborate rituals and etiquette surrounded the meal; it was an important way for the king to demonstrate his wealth and status, and do honour to his important guests. The seating arrangement for a meal was determined according to rigid rules of precedence - the more important you were, the closer to the king you were sat. Women and men would be interspersed where possible.

Media dinnertime, from the Luttrell Psalter

It was considered polite to wash your hands before eating; a bowl of water might be set out next to the entrance to the hall to allow this, or the servants would bring ewers of water to each guest. Washing your hands between courses was also important - since the fork had not yet been invented, so people picked food up with their fingers. (Though spoons were used for soup and broth, and knives for cutting.)

Rather than plates, food was often eaten from 'trenchers', which were large, thick slices of slightly stale bread. These soaked up the juices from the food, and if you were especially hungry you could eat them as well. The meal would have multiple courses, and each course would often see several different dishes placed on the table, from which you could sext as much or as little as you liked of each. It was considered polite to serve the person sitting next to you before yourself, if they were of a higher rank than you.

The first course of the meal was often boiled or stewed meat - pork, chicken, mutton and venison being most common - prepared with an elaborate range of strongly-flavoured sauces, herbs and spices. On fast days, fish was served instead of meat - eels and lampreys, herring or pike, with more of the elaborate sauces and dressings. After the first course, fruit or nuts might be served to clear the palate.

The second course would be roast meat - often venison or game from the hunters, although this was an opportunity for extravagant hosts to impress their guests by serving exotic meat - roast peacock, for example. Salmon, turbot or lampreys might be served on fish days. Vegetables such as leeks, onions, peas and beans would accompany the meat, though often incorporated into sauces and pottages rather than being served separately. Bread was also served, and was often graded into qualities (the whiter the bread, the better) and given to guests of the appropriate status.

The third course would be fruit-based dishes - quinces, damsons, apples, pears, other fruits depending on season; often baked or candied or made into compotes. Small, expensive meat dishes might also be served such as roast sparrows or pickled sturgeon. Finally, cheese would be served at the end of the meal.

To drink, there would be either wine or beer. Wine was considered the higher status drink, so you could expect it to be served at a royal banquet - while the servants and lesser guests would get beer. By modern standard media wine was very rough; it had to be drunk the same year it was made (no corks and no glass bottles). As a point of interest, in the year 1363 King Edward III of England's royal household got through 170,310 gallons of wine, most of it shipped over from Bordeaux.

Both during and after the meal there would be entertainment. Jesters actually did exist; from what we know of the media sense of humour people tended to enjoy slapstick, sarcasm and practical jokes, and could be rather cruel in their humour. Actors, jugglers and acrobats might also be hired to provide entertainment. Music, however, was perhaps more common; musicians would play lutes or harps or other instruments, and minstrels would sing songs and ballads. After the meal was over some of the nobles present might also give a performance of a song or poem, if they had the talent. Composing your own poem was considered a notable achievement - though we know that some noblemen paid professional troubadours to write songs for them, which they then passed off as their own!

A group of Italians from Siena dancing in about the year 1340, to the music of a tambourine.

There might also be dancing once the tables were pushed aside. Party games such as blind man's buff were popular. Less energetic nobles might play chess or backgammon, or gamble with dice. Playing cards reached Europe towards the end of the 14th century. As for sport, bowling became so popular in the 14th century that several kings tried (unsuccessfully) to ban it since it interfered with archery practice. Jeu de paume, the ancestor of tennis, was also popular - it was played with a gloved hand rather than a racket. Football was considered a peasants' game, and cricket hadn't yet been developed. Various martial practices such as fencing, tilting (jousting practice) and archery might also be engaged in. People might also go for a walk or a ride outside if the weather was fine.

The second meal of the day would be served at the end of the afternoon, being smaller and simpler than dinner. The evening was usually spent relaxing; and people generally went to bed early so they could be up first thing in the morning, and make maximum use of daylight.

,牛津大学现代史硕士(1985)

中世纪的国王们花了很多时间在他们的王国里穿梭,从一个地方到另一个地方。臣子的职责之一是在国王带着随行人员选择性访问时提供招待--这可能会非常昂贵,因为国王总是带着与他们地位相称的大量卫兵、大臣、仆人和同伴一起旅行。事实上,这种访问的目的之一是确保臣民们知道他们的国王是谁,并让他有机会亲自视察领地。

不过,为了便于描述,我们将假设国王在他所拥有的某个城堡的家中。我们还假设我们谈论的是中世纪盛期(1200-1350年左右)的西欧国王。

城堡里的国王或领主,以及他的妻子,往往是唯一拥有自己的私人卧室的人--即使在这里,"私人"也是一个相对的术语,因为通常会有一两个仆人在同一房间的小床上过夜,以防国王在夜间醒来有什么需要。这间卧室被称为"solar(太阳能)",因为它通常建在堡垒的大塔高处,有窗户让阳光照射进来。墙壁可能是石头的,粉刷过或抹过灰,并挂着挂毯以防止气流进入,地板是木头的;当时欧洲还没有引进地毯。

随着时间的推移,家庭中的高级成员拥有独立的卧室变得越来越普遍;但这还是没有成为标准。大多数人都睡在大殿里,如果是仆人,则睡在他们自己工作场所(厨房、马厩等)的地板上。

国王的床是木制的--而且可以拆卸,以便国王在旅行时可以带着它。弹簧是用皮革或绳索制成的,床垫和枕头是用鹅毛填充的亚麻布,床通常是"四柱"设计,亚麻布窗帘可以拉开,让人觉得跟睡在几米外的仆人有点隐私。似乎人们通常都是裸睡的(不管怎么样,对于那些买得起暖床的人来说)。

一张带顶篷的中世纪床——这张画像的历史可追溯至 1400 年左右,展示了桂妮维亚女王将兰斯洛特爵士拽到她的床上。

醒来后,国王和王后会在仆人端到卧室的一碗水中洗手和洗脸。厕所("privy chamber")通常是建在塔楼墙壁上的一个小房间,上面有一个简单的孔,座位悬在护城河上。洗澡或淋浴并不是每天都要做的事情--加热和用水桶从井里提水是非常费力的,所以洗澡被认为是一种特殊的待遇。

然后,国王会自己或在仆人的帮助下穿上衣服。典型的内衣是一双亚麻布"胸罩"(宽大的内裤,用绳子系在腰上)、羊毛"长筒袜"(长筒袜与内衣一样用绳子系着),也许还有一件亚麻布"罩衫"(衬衫)。然后是外衣,这通常是一件袖子又长又宽的及地的衣服,从头上套入,一直垂到地上。这是一种身份的象征--需要工作的人才穿较短的外衣,让他们的腿部可以自由活动。另外,虽然大多数外衣--即使是贵族的外衣--都是由羊毛制成的,但国王可能会穿一件丝绸或天鹅绒甚至棉花(比丝绸更昂贵)的外衣来炫耀他的财富。第二件外衣或"surcoat "通常穿在第一件外衣外面--它通常整体比较短,袖子又短又宽,有时尚意识的人会确保上衣和下衣的颜色相得益彰。最后,在脖子上系上头巾或斗篷--虽然这可以拉到头上来让耳朵保暖,但它的主要目的实际上是装饰;它们可以用昂贵的毛皮或珠宝来修饰。再穿上鞋子和束上腰带,就完成了这套衣服的穿搭。没有口袋--你可以把东西塞进袖子里,或在腰带上挂一个小袋子。

这个时候女性的衣服和男性的衣服没有什么不同,只是她们的内衣不是衬衫和马裤,而是亚麻布的短裤。妇女的外衣通常是无袖的,有时还在两侧剪开,以突出她的身材。此外,已婚妇女在公共场合要用布围巾、帽子或头巾遮盖头发;未婚妇女则不遮盖头发,经常用珠宝夹夹住头发。

1300年左右的贵族服装风格--长及脚踝的长袖外衣,外面再穿一件短袖或无袖的外衣。

穿好衣服后,国王会去他的私人小教堂,在那里聆听弥撒。然后,他可能会到大殿与他的贵族和随从一起开斋(即吃早餐)。这通常很简单:面包和啤酒。(非常淡的啤酒,不是你灌两瓶就会醉那种。)许多人根本不吃早餐,而是等到晚餐时再吃,而晚餐一般在早上11点左右提前供应。

大厅通常覆盖城堡的整个一楼(一楼用于储存,出于防御的目的,没有门窗)。房间的中央或靠墙的地方会有一个壁炉。大厅的一端有一个高台(离入口最远处),国王的宝座就摆在那里,有时上面还有一个天幕,还有为他的家人、尊贵的客人和最重要的顾问准备的不太引人注目的椅子。用餐时,大厅里会摆放长椅和木桌,桌子上铺着干净的白布。之后,长椅可以被推到房间的两侧以腾出空间--晚上,许多城堡的工作人员,甚至是那些高官,会睡在这些长椅上。

国王的一天没有固定的作息时间,但一个有良知的统治者会有很多公务要处理。这可以分为两类--国家事务和庄园管理。

国王可能会与他的议会--王国中最有权势的男爵和主教,以及他的首席部长,如司库、大法官和元帅,进行政策讨论。他将发布命令,并由皇家文员记录下来。他可以主持正义--国王被认为是王国的首席法官,虽然这项任务通常被委托给别人,但国王保留了亲自审理案件的权利。他可以听取臣民的请愿和申诉,以及要求他给予他们恩惠或代表他们使用权力的请求。通常情况下,后两项任务是为特殊场合保留的--国王会在城堡或大厅里开庭,并召集他的贵族和人民到他面前,以便他能"征求他们的意见和建议"并主持正义。这些正式会议最终发展成为了议会制度。

庄园管理是至关重要的,因为国王是全国最大的土地所有者。与人们的普遍看法相反,中世纪的皇家收入大多不是来自税收(通常只有在战争等国家紧急情况下才会征收),而是来自国王的佃户和使用其财产的人的过路费、租金和收入。监督佃户和管理收入是一项重要的工作,一个负责任的国王会花很多时间和他的管家一起查看账目并监督他们的决策。

如果国王当天没有公务要做,他可能会去打猎--这是一种非常受贵族欢迎的消遣方式。大多数打猎是在马背上进行的,猎物是鹿或野猪。一个专业的猎手带着一队狗将猎物赶出来,然后国王或他的客人和同伴将用长矛或弓箭杀死猎物。鹰猎和猎鹰也是很受欢迎的消遣方式--对于女士和骑士来说都是如此。杀死的猎物通常会在晚餐时间出现在皇家的餐桌上。

一天中的主餐通常很早,在正午之前就开始了,并会持续几个小时。会有精心设计的仪式和礼仪围绕着这顿饭;这是国王展示其财富和地位的重要方式,也是对重要客人的尊重。吃饭时的座位安排是根据严格的优先规则决定的--你越是重要,你坐得越靠近国王。在可能的情况下,女性和男性会穿插坐在一起。

中世纪的晚餐时间,来自勒特雷尔诗篇

吃饭前洗手被认为是一种礼貌;在大厅的入口处可能会摆放一碗水,以便于洗手,或者仆人会给每个客人送上水壶。在两道菜之间洗手也很重要--因为当时还没有发明叉子,所以人们用手指拿起食物。(虽然汤和肉汤用的是勺子,切菜用的是刀子)。

人们通常不使用盘子,而是用"掘沟"来吃食物,掘沟是又大又厚的略显陈旧的面包片。这些面包吸收了食物的汁液,如果你特别饿,你也可以吃这些面包。这顿饭有多道菜,每道菜往往会被分成几盘放在桌子不同的位置,你可以从中选择你喜欢的每道菜,或多或少。如果坐在你旁边的人的地位比你高,那么在你自己之前为他们服务被认为是一种礼貌。

第一道菜通常是煮或炖的肉--猪肉、鸡肉、羊肉和鹿肉最常见--用各种味道浓郁的酱汁、草药和香料精心准备。在禁食日,人们用鱼来代替肉--鳗鱼和灯鱼、鲱鱼或梭鱼,并配以更多精心制作的酱料和调味品。在第一道菜之后,可能会提供水果或坚果来清理味觉。

第二道菜是烤肉--通常是鹿肉或来自猎人的猎物,这也是奢侈的主人通过提供异国情调的肉类--例如烤孔雀--来给他们的客人留下深刻印象的机会。鲑鱼、多宝鱼或灯笼鱼可能会在捕鱼日被供应。韭菜、洋葱、豌豆和豆类等蔬菜会与肉一起食用,但通常会被纳入酱汁和摆盘中,而不是单独食用。面包也有供应,而且通常按质量分级(面包越白越好),并提供给有适当地位的客人。

第三道菜是以水果为主的菜肴--榅桲、李子、苹果、梨,以及其他取决于季节的水果;通常是烘烤、蜜饯或做成果酱。小而昂贵的肉类菜肴也可能被供应,如烤麻雀或腌制鲟鱼。最后,在用餐结束时还会提供奶酪。

饮料方面,有葡萄酒或啤酒。葡萄酒被认为是地位较高的饮料,所以你可以期待在皇室宴会上有葡萄酒的供应--而仆人和地位较低的客人则会得到啤酒。按照现代标准,中世纪的葡萄酒是非常粗糙的;它必须在酿造的当年就喝掉(没有瓶塞,没有玻璃瓶)。有趣的是,在1363年,英国国王爱德华三世的王室用了170310加仑的葡萄酒,其中大部分是从波尔多运过来的。

在用餐期间和用餐之后,都会有娱乐活动。宫廷小丑确实存在;根据我们对中世纪幽默感的了解,人们往往喜欢滑稽、讽刺和实用的笑话,而且他们的幽默可能相当残酷。演员、杂耍者和杂技演员也可能被雇用来提供娱乐。然而,音乐也许更常见;音乐家会弹奏琵琶或竖琴或其他乐器,吟游诗人会演唱歌曲和歌谣。宴会结束后,一些在场的贵族如果有天赋,也可能会表演一首歌或一首诗。创作自己的诗歌被认为是一项显著的成就--尽管我们知道有些贵族付钱给专业的吟游诗人为他们写歌,然后他们把这些歌当作自己的歌!

大约在1340年,一群来自锡耶纳的意大利人伴随着手鼓的音乐跳舞。

等到桌子被推到一边,可能还会有舞蹈。派对游戏,如捉迷藏,很受欢迎。没有那么多精力的贵族可能会玩国际象棋或双陆棋,或者用骰子赌博。14世纪末,扑克牌传到了欧洲。在体育方面,保龄球在14世纪变得如此流行,以至于一些国王试图禁止它,因为它干扰了射箭的练习,但没有成功。网球的祖先“Jeu de paume”也很流行--它是用戴着手套的手而不是用球拍来打球。足球被认为是农民的游戏,而板球还没有发展起来。人们还可能从事各种武术练习,如击剑、摔跤和射箭。如果天气好,人们还可能到外面散步或骑马。

一天中的第二顿饭将在下午结束时供应,比晚餐要少而简单。晚上通常是在放松中度过;人们一般都会早早上床睡觉,以便在早上第一时间起床,最大限度地利用白天的时间。

Pad Murray

So during this period how would the King work meetings with the parliament into his schedule? Did he go to Westminster on a regular basis, would they come to him (daily, weekly, etc), or did he only meet them when he absolutely needed to?

那么,在这一时期,国王是如何将与议会的会面纳入他的日程安排的?他是否定期去威斯敏斯特,臣子是否会定时来找他(每天、每周等),或者只有在国王有绝对需求的时候才会见他们?

Stephen Tempest

Media parliaments were special events, not a permanent institution. The king would summon a parliament to wherever he happened to be staying that year — it wasn't until the 1400s that Westminster became the regular place for them to be held.

Personal invitations ('writs of summons') would go out to the most important lords and bishops, and sheriffs would be ordered to organise elections. Usually between 1 to 3 months later everyone would assemble. There'd be lots of ceremony as the king welcomed them, they paid allegiance to him, and he told them what he's summoned them for (almost inevitably, this would be "I need money").

As I understand it,. when Parliament was in session the king would normally sit with the Lords discussing affairs with them; the Commons would meet separately and submit petitions and draft bills for the consideration of the king. This was as much due to numbers as questions of social status (though that was important too); there were normally fewer than 50 lords present with the king, so it would be a working meeting.

Parliament would usually only be in session for a month or two. Then the king would dissolve it and everybody would go home again. There was no rule on how often Parliament should be summoned; in wartime it tended to be fairly regular (yearly or at least every couple of years), in peacetime multiple years might go by before there was a need for another parliament.

中世纪的议会是特殊事件,而不是一个永久性的机构。国王会在他当年碰巧停留的地方召集议会--直到14世纪,威斯敏斯特才成为举行议会的固定地点。

个人邀请函("传票")会发给最重要的领主和主教,治安官会被命令组织选举。通常在1至3个月后,所有人都会聚集在一起。当国王欢迎他们时,会有很多仪式,他们向国王效忠,国王告诉他们他召集他们的原因(几乎不可避免的是,这将是 "我需要钱")。

据我所知,当议会开会时,国王通常会与上议院坐在一起讨论事务;下议院会单独开会,提交请愿书和法案草案供国王审议。这既是由于人数问题,也是由于社会地位问题(尽管这也很重要);与国王一起出席的上议院议员通常少于50人,所以这将是一次工作会议。

议会通常只开一两个月的会。然后,国王就会解散议会,大家又会回家了。没有关于议会应多长时间召开一次的规定;在战争时期,议会往往是相当定期的(每年或至少每两年一次),在和平时期,在需要召开另一次议会之前,可能距离上一次已经过去多年。

Diana Dubrawsky

I was taught in college that one way the king collected taxes was by traveling about and making his nobles pay for the court's upkeep: makes sense, since many eataes were "cash poor." The cost of feeding the entourage could be ruinous, and if a king really wanted to bankrupt his vassal, he could extend the court's stay indefinitely.

我在大学里接受的教育是,国王收税的一种方式是通过旅行,让他的贵族们支付宫廷的维持费用:这是有道理的,因为许多国王是"现金穷人(名义上富有,但是拿不出很多现金)"。养活随行人员的费用可能会很高,如果国王真的想让他的臣子破产,他可以无限期地延长宫廷的逗留时间。

Stephen Tempest

True - though the idea of bankrupting a noble by staying with them over-long is something I associate more with the Tudors (Elizabeth I in particular) than media kings.

确实如此--尽管通过长期与贵族呆在一起而使其破产的想法,我会更多地将其与都铎王朝(尤其是伊丽莎白一世)联系起来,而不是与中世纪的国王联系起来。